We’ve still been keeping busy with our Alabama History project and field trips, but I’ve been waiting to catch up on posting about them until I could share some fun news: a dear friend, Carla Jean Whitley, jumped onto our Alabama History bandwagon a couple of weeks after we started. She is an author of books about Alabama history and a journalist for al.com (The Birmingham News.) She and Ali have teamed up to document our year’s journey, through Ali’s eyes, for the news. The first article in the series published last week.

Carla Jean and Ali have bonded over their love for reading, being the oldest child, using Snapchat together, and more. Be sure to keep up with Carla Jean’s exciting and beautifully written series, Sweet Home History, to gain more perspective on what we’re learning.

We had several field trips in a row to appreciate the Native American history in Alabama. Our first was to Russell Cave, Alabama’s only National Monument.

Russell Cave is at the Northern Edge of the state in the small town of Bridgeport, and has an interesting and extremely old history of the Native American people. Cave archaeological finds date people groups using the caves back to 10,000 years ago.

Luke Mason was our guide, and he was a fantastically knowledgeable and animated park ranger. Being Cherokee Indian himself, he was able to add insight and personal experience to our tour.

Although the cave itself is inaccessible to the public because of its status as an important archaeological site (and to protect the bats that live inside),

it was still such a fantastic learning experience as Luke told us how the cave was used by many generations of Native Americans for shelter and life.

To illustrate the richness of the archaeological value of the cave, he stepped across the barrier, dug around in the dirt for about 30 seconds, and unearthed some artifacts. I’m positive he told us exactly what they were, but my mind did not retain those fascinating facts for you.

The kids were given a Nature Scavenger Hunt sheet to fill out while we were on our tour, and they got about 75% of it completed. But they’re serious at Russell Cave – they sent the kids back out until they found everything listed. Then they let them take their National Park Junior Ranger Pledge,

And awarded them with Junior Ranger badges.

I had never heard of Russell Cave before I started researching for this project, and it was such a great find. The museum and the park rangers offered so much fantastic information about early people groups in Alabama, and there were several things that Ali learned there that carried on with her through our next field trip stops.

——————-

We waited around a few weeks to do our next trip so that we could go to the Moundville Native American Festival. And although the Moundville grounds and Museum are worthy enough of a trip,

the Native American Festival really made the experience come alive.

There were storytellers, musicians who also told gripping stories to go along with their songs,

demonstration booths,

and vendors.

Noah chose to buy a bow and arrow, but was too shy to get lessons from the man who handcrafted it. Ali and Carla Jean, however, did not pass up the opportunity.

Ali chose a flute, also directly from the man who crafted it. She’s still practicing QUITE regularly.

They loved going up to the top of the highest mound where the Chief of Chiefs would preside over the tribes. It was easy to imagine all of the commotion below when they explained the scene.

While we were on the mound, Noah spied a shooting range. Since we’d gotten in trouble earlier for letting Noah shoot his bow and arrow (oops – I was given a sheet of paper that I assumed had the contact information of the craftsman but actually said that bows would be confiscated immediately if shot on the premises), we decided to go down and see if we were allowed to practice there.

It turned out to be the weapons demonstration area, but since no demonstration was currently happening, the kind gentlemen gave Noah one-on-one shooting lessons.

The lessons worked, too – I was able to capture him getting a bullseye before the safety-tipped arrow bounced off. Never has my son ever been so thrilled with my photographical abilities.

The other gentleman at the weapons demonstration tent, Bill Skinner, decided that Ali needed to learn to throw giant, man-sized darts with an atlatl. After explaining the physics and math behind leverage and velocity then demonstrating how it worked, he presented her with the weapon.

She immediately fell in love with this Wooly-Mammoth-Killing Apparatus and continued her atlatl practice for some time.

She recalled learning about the atlatl from Luke at Russell Cave, which I found pretty cool because I thought I’d never heard of one before. At least someone is listening.

She’s definitely interested in purchasing or building one of her own. Can you open carry an atlatl?

He also gave her club lessons, explaining carefully that these weapons were meant to break bones, not bruise – and exactly where to hit to break those bones (Head, Hip, Knee – in case you were wondering.)

The girl is prepared for anything now.

——————-

Our transitional stop from Native Americans to early settlers was Fort Toulouse / Fort Jackson in Wetumpka.

Fort Toulouse was actually a French outpost in 1717 – the easternmost point of the French Louisiana Territory. They set it up so that they could trade easier with the Creek Confederacy, especially favoring the Alibamu tribe.

This went along fantastically until the British won the French-Indian War and chased the French away.

In the early 1800’s, Fort Jackson was established by Americans to use in the Creek Indian War. After winning, the American Government took over 20 million acres of land from the Creek Indians, much of which is now Alabama.

(Ali yelled out upon reading the above fact, “AGAIN?!?! HOW MANY TIMES ARE THE AMERICANS AND BRITISH GOING TO TAKE LAND FROM THE INDIANS?!?”)

(I could only say “I know, right.”)

The reason this particular piece of land has been so valuable over many centuries is because it is in the pie piece of land where the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers converge. So it is beautiful, fertile, and of strategic importance in military terms.

One of the first things that struck us was that every tree was coated in Spanish Moss. We seemed far too west and north for it to be there, and we wondered if it had been transplanted when the fort was originally created.

We didn’t discover the answer, but we did appreciate the elegance it added to the site – we felt as if we had found a wormhole to Savannah or Charleston.

There was a beautiful reproduction of Fort Toulouse – the nice part about visiting a reproduction for is that you’re allowed to climb on and explore it – because you’re not about to ruin some 300 year old piece of history.

And climb my kids did.

They even laid siege to the fort…

And the buildings inside.

We were nearly the only people at the entire historical site, so the kids really enjoyed the opportunity to run around and explore on their own schedule.

I personally appreciated the beautiful metalwork on all of the hinges – whether true to the original or not, I thought it was a nice touch for a French Fort that was meant for peace rather than war – the Fort of Love.

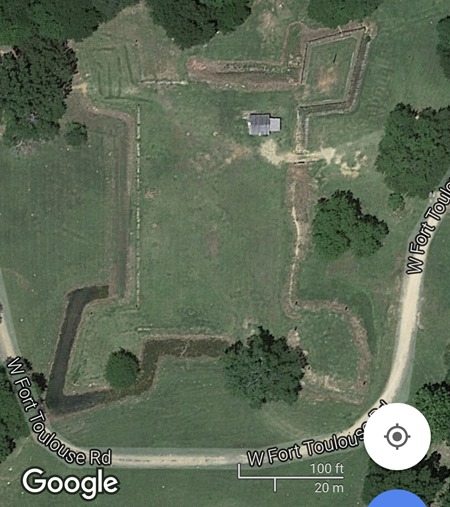

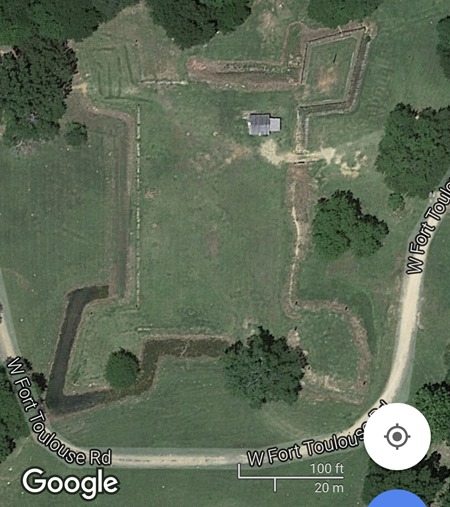

Fort Jackson, the American Fort, still had remnants of its moat and the protections thereof.

(In fact, the satellite imagery of Fort Jackson is pretty cool. They designed moats so very fancily.)

There wasn’t too much to see at the Fort Jackson site, but by far the favorite place to visit in the kid’s opinions was the reproduction Native American Village.

It included examples of winter houses,

and a summer house.

The beds were made of bamboo and were surprisingly comfortable and cool. Perhaps we should reconsider artisan bamboo beds.

Ali tried out the top bunk,

While the rest of us stayed on the lower levels.

(Really. I did try it out too. But alas, no selfies to prove it.)

The last stop on our self-guided tour was a Native American mound, smaller and more overgrown than Moundville’s, but fun to explore. Dated 1100-1400, it was by far the oldest feature of this historied piece of land.

The unexpected thing about all of these trips is how they’ve woven together in quite the unplanned ways. We learned about the atlatl at Russell Cave, then got to try one at Moundville. We learned about the importance and uses of the mounds at Moundville, then got to see another one at Fort Toulouse. I can only hope that the field trips themselves continue to do a better job of educating my children than I could ever plan for.

If you’ve enjoyed following Ali’s reports, you can flip through all three included in this post here:

russell-cave-moundville-fort-toulouse-field-trip-report